Storied Past Comes To Light: Frank Winiarski, Time And Old Wethersfield

“In time I began to understand that it's when you start writing that you really find out what you don't know and need to know.” — David McCullough

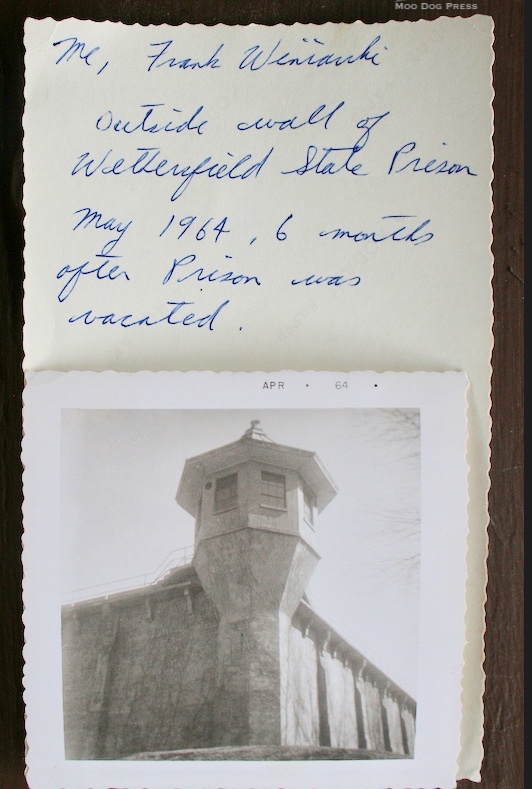

Place and time. Underfoot, paths and a prison. The state prison. Gone now, but not forgotten.

Frank Winiorski shares a page of his collection. The typed caption below the old image is as follows: “The burying ground is in the rear of the prison, a little less than midway from it to the main road between this city and Wethersfield, and can be really seen from the horse cars. Although there are no slabs to mark the resting place of the prisoners, yet the spot where the friendless convicts are interred overlooks a scene of great beauty.”

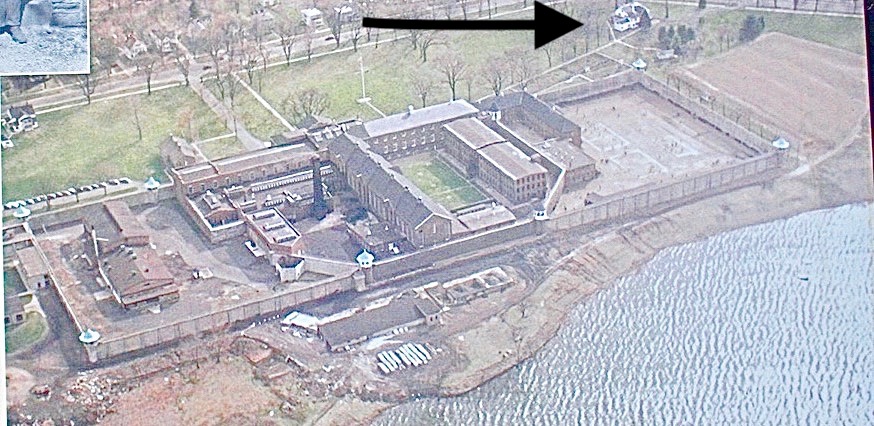

The arrow points to what is now known as the Solomon Welles House in Old Wethersfield. The Cove is at bottom right; the image of the extensive complex is a detail of interpretive sign 15 about the state prison cemetery is placed at Cove Park. Excerpt from interpretive sign 15 now placed on site: The first cemetery, operated from 1828 to 1888, was located nearby, but all traces of it have since been erased. While the majority of its residents are convicts there are also two individuals who died to typhoid interred here. Another noteworthy interment was inmate Prince Mortimer, an enslaved African American convicted of attempted murder of his master by arsenic poisoning who died in 1834 at the age of 110.

“I think it's extremely important that people in our time know about the history and what the Wethersfield prison represented in what times were like because in the 19th-century conditions at any state institution were appalling. They didn't have any progressive reform until the 1890s. In the old days Wethersfield operated under the Auburn system where you had complete silence,” said Frank Winiarski, who grew up across the street from what was then the warden's home, but today is known as the Solomon Welles House in Wethersfield, Connecticut.

“A lot of the guards at the personnel were from Wethersfield, so it really contributed to the local economy,” he said.

And yes, people escaped.

“The first escape occurred in March of 1831, where a lady named Thurzia Mansfield who worked in the Warden Amos Pillsbury's kitchen, and when nobody was looking she simply walked out of the kitchen and the prison door. She was apprehended about an hour later going towards the center of Hartford. She was the first escapee of the prison,” said Frank Winiarski. “There was also a lady named Abbey Jane Wade. She was arrested in 1857 for stealing a $500 bank note from a Mr. Kennedy of East Hartford, Connecticut. She took it out of his pantaloons or ‘baggy pants' – so she was sent to Wethersfield. After 3 years, apparently she had had enough. When the matron wasn't looking, Abbey Wade slipped out of her cell and went out the back of the prison. She was missing for three weeks but was found hidden under the barn of Winthrop Buck, where she had hidden herself in a wooden box. When they apprehended her, her clothes were all dirty and ripped. She explained how she said she survived – sustained by taking milk from the warden's cows – the warden at the time was Leonard Welch and he had a barn next to what became the wardens house. And she also had broken back into the prison by use of of an elm tree which was up against the wall – and took bread to eat.

“In 1872, an inmate named Charles Gilbert was employed in the prison boot factory and he escaped one evening by scaling the prison wall, which was 20 feet tall and he was caught one year later and put back in prison but was eventually released, but he was so bold he took a rope with a grappling hook and at nightfall scaled the wall and was caught trying to steal a pair of boots from the boot shop.

“Throughout Wethersfield's history there were about 150 escape attempts, only three or four managed to stay of prison for the rest of their lives, they were never heard from again. All the rest were apprehended usually within hours days or weeks.

“There was an escape in 1913 by a prisoner named John Dewey, he was employed in the shirt shop. Every week the prison had a wagon and two horses come in, men who would load up wooden cartons from the work of the week. This man figured out the weight of the prison shirts and he deducted his weight from what was in the boxes. He managed to get a baling wire attached to the inside lid of the box, so he got in the box and closed the lid. The other prisoners unloaded these boxes and they were sent out of the prison to the Valley Railroad. So the man escaped, but was caught later.

“A man named Frank Guidi was a trustee working on the prison grounds, he simply walked off and it's believed a car was waiting for him. He was never seen again. That occurred July 12, 1922. A man from Lithuania named Anthony J. Velicka, was accused of robbing a tailor in Hartford on Albany Avenue and apparently he wanted to escape so badly he boarded a Connecticut company bus, he simply went behind a maple tree and he took off his prison shirt and pants and underneath he had civilian garb, he already had the escape planned. They found his prison clothes under the tree and he was never found, this occurred in 1957.

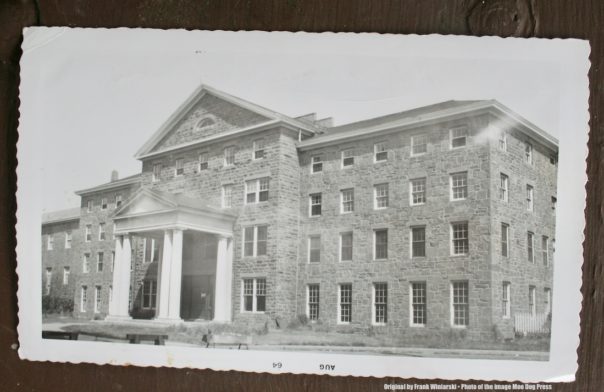

Imposing and once it stood in Wethersfield. Aug. 64 is noted on original photo by Frank Winiarski in this image of it.

“Trustees are referred to as a prisoner who has been given the trust of the prison administration. At Wethersfield trustees were men who served short sentences, they weren't a threat to the community. They may have committed a crime like auto theft or burglary and were trusted by the warden to go outside the prison with guards and do maintenance work.

“Wethersfield was chosen chiefly on the urging Judge Martin Wells, he was a judge for this area. He lived in what became the Webb house for awhile. Wethersfield was picked because it was right on the Connecticut River. They wanted something centrally located and Wethersfield was only 4 miles south of Hartford. Also, because there was thought to making bricks by the prison inmates. The brick making did not pan out because it was proved to be unprofitable, turned out there was not enough clay in that area of the cove,” said Winiarski

Request made March 4, 1957 by Edgar Penn inmate 17567 serving 8 – 12 years – made to Rev. Camp. “Would you be as kind to send some cut flowers to my mother as her birthday is today and I wasn’t able to send them … I would like to send about $6.50 worth . . .

“At the time the prison opened the population being moved from Granby was exactly 121 inmates; the one-day journey of 81 prisoners was done by foot. There were four women prisoners who traveled in a wagon drawn by horses. A man who was reportedly 103 years old rode in the wagon with the women. The rest were put in groups of 10 and were chained by the ankles and chained by the wrist.

“A lot of the public gathered along the road going from Granby all the way down to Wethersfield to watch this happen, it was like a circus atmosphere, a spectacle. They did reach Wethersfield on Sept. 30, camped out in front of the prison grounds and they stayed there until sunrise. That morning, the prison itself was formally opened, Oct. 1, 1827, when Warden Pillsbury turned the large iron key to open the main gate.

“The prisoners were read the rules and regulations. Now it was really an improvement since Newgate prison had been a subterranean copper mine and when they came to Wethersfield you had something above ground. A lot of the guards and personnel at the prison were Wethersfield citizens. Some guards boarded with the warden in the prison complex.”

When brick making proved unprofitable, “they ended up making clock parts, Britannia wear. And, believe it or not, pistols and rifles for a brief period of time. They also made boots, they made shoes. They made wagon wheels for the general public as well as for their own use.”

“The inmates worked from sunup to sundown, six days a week, about 16 hours a day, with a half hour each for breakfast, lunch, supper. The lights were out when the sun went down.”

“Both male and female inmates worked: men as blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, tailors; the omen as domestic workers and cigar-makers. The prison was built on 44 acres at the edge of Wethersfield Cove and the grounds included the 1774 Solomon Welles House, used as the Warden's residence. Beginning as a single building, over the course of its 136-year history many more buildings and workshops were constructed until it became a “hodgepodge” of ill-matched structures within the surrounding walls.” – Wikipedia

“There was a place where visitors from the general public were allowed to enter to watch the workings of the prison. The state charged 25 cents to tour the prison when it first opened. From 1827 to around 1911 or so, because the warden at the time prohibited the tours because he thought it was degrading to the prisoners and intruded on their privacy.”

Not an easy life at all.

“The inmates worked from sunup to sundown, six days a week, about 16 hours a day, with a half hour each for breakfast, lunch, supper. The lights were out when the sun went down.”

— The Winsted Citizen (@WinstedCitizen) October 22, 2023

Walkers at The Cove; many have no idea about the many-layered past in town and around the cove. CB/MDP

Another quest remains in progress. Liberty Street, Liberty Road, Meriden. Research. Images of work in progress, building the old Meriden High School. Bleach houses, bleach field, trails in Deep River; an update on new interpretive signage and why.

Editor's note: Portions of this story originally appeared in 2018.

My painting 'Dog' egg tempera, watercolour, gesso

For me, dogs are the most incredible of animals and my life would be unimaginably poorer without sharing it with one – or two. #dog #painting #drawing #animals #watercolour #nature pic.twitter.com/Qd4OKS3AGy— MaryAnne AytounEllis (@AytounEllis) October 21, 2023