Then & Now: Walk Wethersfield, Then A Quest

“Seeing is as much the job of an historian as it is of a poet or a painter, it seems to me. That’s Dickens’s great admonition to all writers, ‘Make me see.’”

David McCullough

Life circles back and around. From a toy camera with film that worked held while standing near fence to try and capture the draft horse teams competing at a fair. To digital sharing with handheld computing devices that accomplish near real-time visual reports from across a state.

For years, knew nothing more about Wethersfield Cove than the parking lot and boat launch area. Then a chapter opened and what were ideas became reality. So much learning, doing, seeing.

“Both male and female inmates worked: men as blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, tailors; the omen as domestic workers and cigar-makers. The prison was built on 44 acres at the edge of Wethersfield Cove and the grounds included the 1774 Solomon Welles House, used as the Warden's residence. Beginning as a single building, over the course of its 136-year history many more buildings and workshops were constructed until it became a “hodgepodge” of ill-matched structures within the surrounding walls.” – Wikipedia

“There was a place where visitors from the general public were allowed to enter to watch the workings of the prison. The state charged 25 cents to tour the prison when it first opened. From 1827 to around 1911 or so, because the warden at the time prohibited the tours because he thought it was degrading to the prisoners and intruded on their privacy.”

Grapes.

“Along the Wethersfield Cove Yacht Club, there was a white picket fence and I would see inmates especially during September and October, go along the fence picking Concord grapes. The prisoners would put the grapes underneath their shirts and they would take them back to the prison, from what I understood, they would put the grapes in fruit jars and let them ferment,” recalled Frank Winiarski, who grew up in the 1950s through the 1970s in Old Wethersfield, Connecticut.

“Our house was right across from the warden's house,” he recalls. “That's now known as the Solomon Welles House. So I lived right across the street from it.” His boyhood home is still there, though Frank now lives in East Hartford. His interest in town history – and the Wethersfield Prison – in particular, is no surprise. But his recall of details and documentation is exceptional.

“Used to be Fridays, in particular, they would deliver large steel milk cans for the warden along with various fruits and vegetables from a prison farm at another location. It was very interesting in that during the summer months, they were cutting the grass with hand mowers and would do a lot of maintenance along the perimeter of the prison. The walls there were covered with ivy and periodically they would take ladders and would trim the ivy within 6 feet of the top of the wall. The guards with this small group of prisoners were not armed.”

“Bugler Jimmy Rondinone would play Reveille in the morning and Taps at night, most people don't know that.”

Of course, Winiarski recalls the sound as part of his observations while growing up in town.

The Solomon Welles House, a stately white two-story structure at Cove Park, now serves as the backdrop for many community events in Wethersfield, including festivals, sports activities, the Wethersfield Farmers Market, picnics. Walkers can skirt the edge of the cove using a path to the popular inlet of the Connecticut River that features a boat launch. And nearly everyone in the state knows the location of the Connecticut Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) on State Street and/or has been on site for registering a vehicle, boat, or for a driver's license update or renewal and other vehicular necessities. What most don't know is that the land on which they walk is the same ground as what once was a state prison facility. Remnants remain for those who look, the land remembers and serves as an overlay of human history.

Back to the grapes that ripen to perfection in September.

“From time to time, the deputy warden said too many of these guys were getting drunk and he wondered how that could be. So the guards would take these 8-foot-long rods and there was a coal pocket within the prison itself on the east side where the boiler room was – and the guards would take these steel rods and poke a coal pocket, probing. Every now and then you could hear a loud ‘pop' – that was a hidden fruit jar with the wine fermenting, it would just break.”

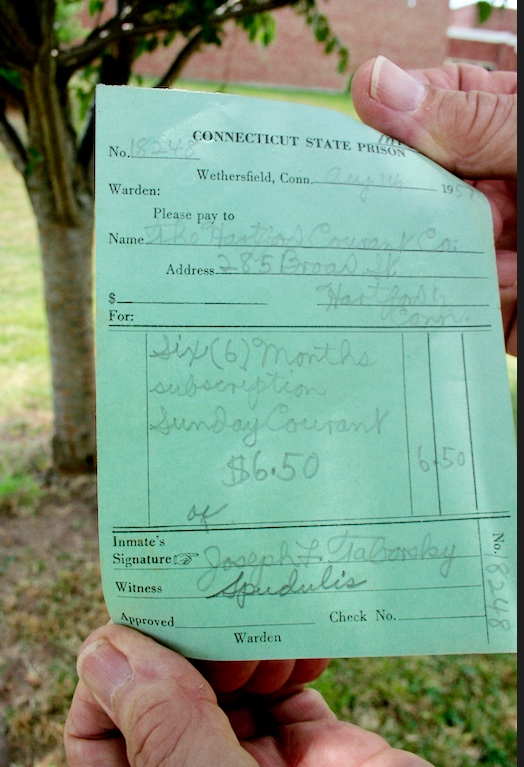

Curious about his surroundings, Winiarski knows much about town and state lore, including Native American history and where artifacts have been found in fields and by walking and looking. He has compiled clippings, photographs, books, uniforms, objects, his own research into a thick file of information. He has also presented lectures on the guards who worked at the Connecticut State Prison while in Wethersfield, 1827 through 1963 at the Keeney Memorial Cultural Center, worked with Wethersfield Historical Society for an exhibit Castle on the Cove.

“Wethersfield State Prison …later demolished and the site turned into a park on the banks of the Connecticut River.” – Wikipedia

“During the fall there would be groups of prisoners outside the warden's house and they would have the old steel rakes, they were raking. I was watching from my house window and they would take two prisoners, they would take usually two prisoners to the guard tower called the warden's tower. It had a steel door 24 inches in width, very narrow opening. A guard would open the steel door and the guard would follow the prisoners up the spiral stairs and once they were in the tower one guard opened another door and they just walked along the top wall which was anywhere from 18 to 25 feet in height, depending on the topography. In the winter, they were shoveling snow with old-style steel snow shovels. The trustees would take their steel shovels and ice choppers and they would have to clear the entire perimeter of the prison, all the walks. This was an ongoing process with any storm so that the guards had to make their round every 30 minutes to make sure there were no escapes. They had to make sure the walks were clear so the guards could walk the catwalks.”

“The prison also had their own laundry where the inmates did the laundry. When we were kids we would go down to the Cove with our sleds or ice skates. The guards would always blow a whistle from the wall, warning us to keep away – it was around the middle, to the rear of the prison where the laundry pipe emptied out. All the water around there was open – on a cold winters day you could see the steam rose from that water, just rising above the ice of the Cove. It was really something.

“This site was so historic. It started off as just one principal building in 1826; the state legislature and the house authorized the building of this prison. Formal construction began on July 1, 1826. A lot of local farmers took part in the construction of the prison, everything was done by hand. There was no mechanization whatsoever.

“The brownstone for the prison came from Portland quarries. The brownstone was taken up the river by barge from Portland, Connecticut, to what at the time was known as Steamboat Landing – what is now the dock I believe where Hess Oil unloads the oil for the tank farms. Wethersfield has the only tank farm on the west side of the river from Long Island Sound up to Massachusetts. Anyway, the brownstone was off loaded by teams of oxen or draft horses and was brought up what was then known as Fort Street because there was a fort constructed in the 17th century on the banks of Wethersfield Cove. The term fort actually is misleading, it was actually a palisaded safehouse from the Indians.

“Because in the 1630s, the tribes were still active in the area. Even after the Pequot tribe was destroyed at Mystic, there were a lot of other local Indians up to time of the King Phillip's War in 1675. So these safehouses were important. Newington had one, Rocky Hill had one, Saybrook had the fort down on the sound.

“Now back to the prison, the iron bars were forged in Salisbury (Connecticut). The locks were fashioned by the inmates at Newgate prison in Granby. The windows were of solid oak with Salisbury iron for the bars. Iron sort of like pegs for corners to the windows.”

Many are brownstone like this classic one, but there is some variation even in the 8 along Whitney Ave: IX is the only one that is not brownstone in that series. Most have an abbreviated county seat reference with Roman numerals, some say “M”, “mi” or no “miles” reference. https://t.co/u0xaNSPlQx

— John C Watson (@watsonjohnc) September 1, 2022

I will never ever ever ever ever ever ever ever ever not be absolutely ENTRALLED by our ever so majestic Tsé Bit'aí.

Had to pullover & take this on my way home after a completely full & productive day.

THIS WAS MY REWARD 😍🥲 pic.twitter.com/zkNz8IUpom

— Graham Tome Biyáál (@gbeyale) September 5, 2023