‘No Hoof, No Horse’ . . . So True, Part Two

Editor's note: The second half of a two-part story from our Horses & Life section that originally appeared in 2012. This interview is among the most memorable over the years for airing how vital is applied knowledge and teamwork for maintaining an equine friends or partner. Technology and imaging have opened up new avenues for diagnostics, yet communication is how all moves forward.

Lameness in a horse is a response to pain.

Lameness in a horse is a response to pain.

That time-tested, oft-quoted “no hoof, no horse” – or as Dr. Michael Stewart, equine veterinarian and owner of Stewart Equine Clinic and River Meadow Farm, will say, “no foot, no horse” – are four words that sum up a biological marvel.

A horse is an animal in motion – be that thundering down a track in competition, pulling a carriage, in an arena, out for a trail ride, or grazing in a pasture. At peak performance, a horse inspires both awe and respect; when lame, dismay.

To heal an athlete with four legs takes time and teamwork.

“The philosophy I go by is that tendons, ligaments, tissues all need to heal in motion,” Dr. Stewart notes. “Yes, there are orthopedic issues and such that require lack of motion. But bones and ligament don't float in space, they are attached to a horse, an individual. Tissue responds to stresses and strains placed upon them. Absence of stress on ligament or orthopedic components through healing create a weaker structure, which in the end which is more likely to be injured again.

“This is no different than with people. After a knee replacement, people are helped to get moving almost immediately because the longer they are immobile, the more difficult healing can be.”

With hoof management, changes to a foot or ankle work to shift the load on ligaments. Shoes can shape a foot, leg, or gait.

“No animal is designed to walk on a nail – and a nail is a horses' hoof, designed for protection in the foot as well as structures which help support the foot.”

To address why the horse is not getting better may call for an MRI or other diagnostics. Dr. Stewart is armed with state-of-the-art mobile ultrasonic, X-ray, and endoscopic digital capabilities. Yet all work-ups start with communication.

“Prior to even touching a horse, it's necessary to have a conversation and get information from caretakers, owners, trainers,” he said. Those descriptions will help with direction in which to look. The back-and-forth relationship between a client and a vet and a farrier is paramount to the big picture of health and optimum capability after an injury.

“In racehorses we'll address a tendon or ligament problem, but it keeps coming back despite therapies,” he said. “And it turns out that the injury was created by arthritis in a right front ankle that caused an overload of the opposite front leg. The horse compensated and that shift created a strain.”

Horses that compete perform under tremendous loads to every parts of their bodies.

Some background on how Stewart came to Connecticut.

“For several years we had a combination of commuting back and forth to New York racetracks and doing Lindy Farm work,” he recalled. Work included Roosevelt Raceway in Long Island, with John R. Steele Associates and the Standardbred industry; at the Meadowlands and Yonkers raceways exclusively, and as full-time vet for Lindy Farms, renown for harness racing achievements.

A farm in Connecticut made sense – for its central location and easy access to transportation choices, universities, clients. Now his practice is 90% sport horses, with about 15% Standardbred racetrack work. Thousands of hoof, foot, ankle, leg, tendons and ligaments seen, felt, treated, assessed do add up to an invaluable resource to draw upon. He specializes in leg and foot problems and sees horses in New York (west of the Hudson River) to Long Island; Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Connecticut.

Note: The horseshoe shown above was found in an old barn in Tidewater Virginia. The mute metal “speaks” when examined by Dr. Stewart: “This is a hind shoe with a full swedge. A farrier has made it into an egg-bar shoe – so-called because the full circle is in the shape of an egg. This would be used for a horse with an upper leg, hip or stifle problem. The shoe would help hold the foot straight as opposed to it twisting as it strikes the ground. The welded-on heel caulk – sometimes called a trailer,” he points out the raised small bar. “Trailers are always on the outside of a shoe so this is a left hind shoe. The full swedge shape and the amount of steel is typical for a Standardbred. A riding horse would have a much heavier and thicker shoe.”

Horse & Life: A Field Report

Note: Part one – ‘Peel The Onion Patience To Pinpoint Equine Pain' linked here.

“In reality, diagnostic work is paired with watching and listening to what the horse is avoiding – trotting or cantering a certain direction, or in a certain activity,” he said.

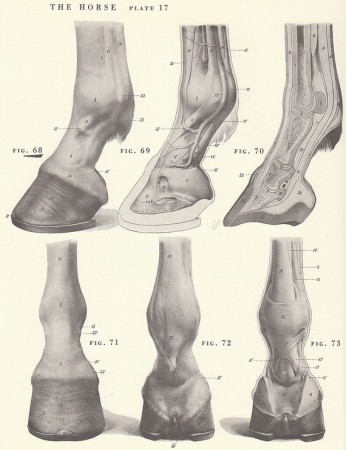

Take laminitis, which literally means inflammation of the laminae that separate the coffin bone and outer wall of a hoof. Lamanie contain blood vessels and nerves and surround the coffin bone as a hoof wall encases it all and supports a horse's weight. Laminitis can run the gamut from mild inconvenience to catastrophic, calling for euthanasia. Just the word can strike fear into a horse owner's being.”It's time consuming and costly what is involved to care for these horses,” he notes.

“Two similar cases can be managed very differently. There is emotional attachment, but also physical ability of each person, plus financial and time constraints. So to understand where the horse and their people are coming from is important.

“The cost of an X-ray and all equipment has gone through the roof as medical devices have improved,” he said. “But the ability to digitize information and have information evaluated across the country and even the world is extremely important. To have a network of veterinarians with additional expertise is an extremely important aspect of mine and every practice.

“My goal is to constantly be stretching my knowledge and imagination in managing lameness issues,” he said.